Of all the creative projects I’ve been working on over the past year, none have received more unexpected enthusiasm and interest than my conlang project; a conlang being a constructed or artificial language. It never ceases to surprise me how much people comment on and seem to enjoy the progression of Ro’tehk, so thank you all for your support.

This is the first language I’ve ever decided to flesh out, so just know that I’m still very much an amateur with a lot left to learn. I do plan on creating at least three conlangs for the CO4 – Ro’tehk, Vorisian, and Vivite – if not bits and pieces of others, so I expect to refine these skills in time. I’m also not bilingual, so most of the rules I use are either straight from imagination or based on scraps of understanding I’ve picked up from trying out foreign languages and then dropping them before I became fluent.

I’ve learned a bit of Spanish, some Hebrew, and a little German. I also spent time some years back reading up on Tolkien’s Sindarin and Quenya dialects and Myst’s D’ni language, but I don’t think you need to have experience with foreign or fictional languages in order to create your own. That said, it certainly helps to have these frames of reference and an exposure to unfamiliar systems, so I’d encourage prospective conlangers to go research at least one language of interest before attempting to build one.

Before I get into my own approach to conlangs, I want to share a few videos from Artifexian, a YouTuber that’s been an important source of information and inspiration. He’s far more eloquent in his explanations of these systems than I am, and if you’re interested in starting your own language, developing a number system, or just in the mood for some cool world-building tips, I’d highly recommend giving his channel a visit.

Step 1: Understand The Culture

There’s not much point in making a language in the first place if you have no culture or people to attach it to. A language is an extension of a people’s ideas, values, and world views, so creating a language before you know who it belongs to can make things foggy when trying to make creative choices. If a culture is short and snappy, its words will likely reflect that tendency, and the same goes for a long-winded or slow-paced culture.

I usually have a decent idea of what my culture’s focus and atmosphere are like before attempting a conlang, but some simple questions to ask might be whether they are a warlike people, religious people, principled people, or a lawless people. What values make them unique? Are they family-centric, or are they lone wolves? Do they believe that the stars are the souls of their lost ancestors, or perhaps they have an unusual focus on manners? Why do they value these things? For pride? For honor? For self-gain? Some of these questions are a bit too in-depth, but you get my point. The mindset of a people will shape the methods of their communication.

I’m building Ro’tehk for a particular culture, and their mindset plays into how these concepts develop all the time. A few major pillars constitute and differentiate the Ro’tehk from the other cultures in my writing, one of the most important being their focus on the concept of time and history. Instead of having a major religious faction steering and flavoring their politics, they have the Archeological Society and the Archivists. These are mostly scientific and historical bodies that regulate the calendar, canon history, and language maintenance.

This public influence creates a culture that is naturally inclined to detail and order, making their language more sensible and clear. This shows through in their vocabulary as well as their sense of grammar and phonetic system. This comes back to their desire to preserve history accurately, and in order to do that, the language must remain consistent so that things are not so easily lost in translation.

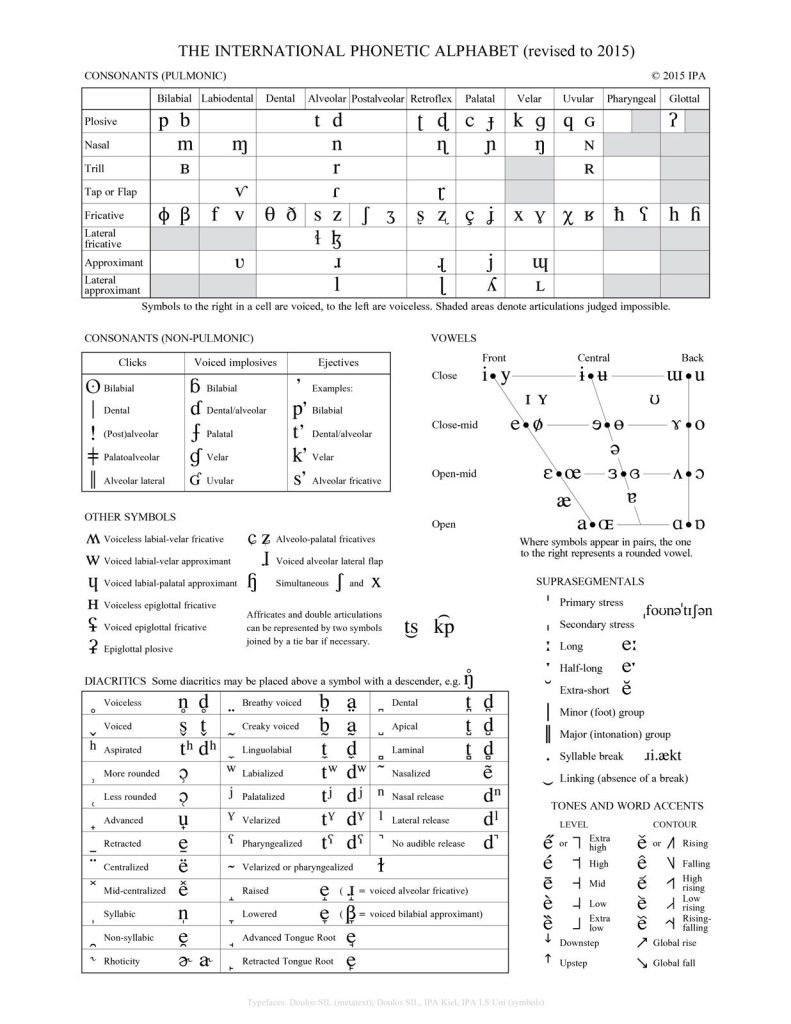

Their focus on time also plays a large role. Instead of feminine and masculine words, Ro’tehk uses past and future words. Words that begin with soft vowels, which are Ahn /a/, Ehn /ε/, Ihn /I/, Ool /Ʊ/, and Uhn /ə/, tend to be used in words that describe something of the “now”, “future”, or “uncertain/incontinuous”. Words like “lush”, “kahnehth”, a description of healthy plant life, would be soft vowel words because it is something happening now that will end in the near future.

Conversely, sharp vowels, which are Ave /eI/, Eelule /i/, Ike /aI/, Ole /oƱ/, and Uum /u/, tend to be used in words that describe something of the “past” or something that is an “unchanging force”. A word like “demon”, “dakehn”, is an example of something that represents both of these ideas. “Green”, “Ka’”, is a “past” word because it is an ever-present idea, and has presumably existed since the beginning of time.

However, as is the nature of all languages, no system is perfect, and this soft and sharp vowel system is not always true. It also requires words to change over time as “future” words slowly become “past” words, and this can create linguistic hitches that are increasingly difficult to solve.

Step 2: Decide On Your Phonetics

There are several ways you can go about doing this, but the easiest is to try and imagine what this language sounds like. Is it soft and melodic like elvish? Or is it rough and barking like orcish (or like German?) What phonemes are required to make these sounds? Keep in mind that there are several sounds that American English doesn’t often utilize, such as the “ñ” in Spanish or the guttural “cha” sound in most Middle Eastern languages. Rs aren’t the only letter that can be rolled, or “trilled” – Bs can also be rolled, though that is rare among human languages. Some Australian and African languages use clicks, though you might have a hard time pronouncing your own language if you decide to use those liberally.

Are there sounds that your language doesn’t use? In Spanish, they have no letter for the English “J”, and pronounce it like an “H”, such as in “jalapeño”. Keep in mind that the fewer sounds your language utilizes, the harder it will be to create a large vocabulary of short words, and the more you may have to rely on inflections, guttural stops, lengthened sounds, and other special linguistic tricks. That said, if you use too many sounds, you will begin to lose distinction between similar-sounding words and things will get muddy in a hurry.

This is the International Phonetic Alphabet, a list of all sounds in the human range. I’m still trying to learn what much of this means, and I’m relying on videos to educate myself on how to use this system.

Once you’ve chosen the sounds you want, you need to decide what type of system they’ll be placed in. There are seven widely recognized types: Abjad, Alphabet, Abugida, Syllabary, Logography, Ideography, and Featural. I’ll be focusing on Alphabetical here since that’s the system I chose for Ro’tehk. If you want to know more about these systems, go back to the videos at the top of the page and watch the first one on Creating a Writing System.

For an Alphabetical system, you need to decide how many of your sounds have a dedicated letter, or if some sounds share the same letter. For instance, the English letter “Y” carries three sounds. “Yes” is the consonant sound of /j/, “City” is the vowel /i/, and “Cyst” is the vowel /I/. You can have one letter carry as many sounds as you want, but the more sounds per letter, the more complicated your word structure and rules for bringing out each sound are going to get, and the easier it will be to misread what is written. Rules will begin to conflict with each other, and phonetics will inevitably break down, but that’s also the most natural state for a language to be in, especially if you speak English. We all know how broken English phonetics can be, yet the language still serves us just fine because we often rely on memorization for spelling rather than constant rules for spelling.

Do some of your sounds have no singular letter? English does this with “th” in “thank” which is /θ/, “th” in “the” which is /ð/, “ch” in “change” which is /tʃ/, and “sh” in “show” which is /ʃ/, forcing these sounds to share a combination of otherwise unrelated letters.

For Ro’tehk, I opted to have one letter for every sound. No letters ever share sounds, so that way when reading a word, no extra phonetic rules or memorizations are applied. This means that the alphabet currently has 34 letters instead of the 26 that English has. This is canonically due to the influence of the Archivists who standardized the spelling several centuries prior and converted their historical Abjadic writing into Alphabetical. The Abjad system was prone to loss of information and illiteracy as vowels evolved over time, so the change was made to more accurately safe keep historical accounts. This is why all but one of the soft vowel sounds appear within or beside the letter “H” – Hyrah; but that’s a discussion for another article.

This is where exposure to foreign languages really helps the creative process along. The idea to add a conversion from Abjad to Alphabet came from my experience learning Hebrew, a historically Abjadic language turned Alphabetical. One of the problems with trying to read Biblical Hebrew is that all the vowels must be inferred by the reader, and if they are inferred incorrectly for any number of reasons, the entire meaning of the sentence or paragraph becomes mangled. The less room a writing system has for misinterpretation, the less likely it will be for information to get lost when being read centuries or eons later.

Step 3: Design A List Of Glyphs

This is probably the best part of creating any language. The appearance of the glyphs and writing systems are the most iconic aspects of any real or fictional language. You may not know the first thing about Japanese, Korean, or Chinese, but the unique characters of Asian scripts can be spotted from a mile away and identified as such. The personality of the language and its speakers can really show through in the choices made here.

Two of my favorite examples of this are Tolkien’s Elvish and Doctor Who’s Gallifreyan. The elegance baked into the Elven font matches perfectly with the artistic and etherial culture of the elves. Gallifreyan is the language of the Time Lords, a race of time-sensitive and rebirth-capable beings, so I’ve always found it clever that their writing is based entirely on circles.

As entertaining as this part may be, it can be difficult to settle on the shapes used to make the script feel unified. One of the best tricks I’ve heard for this problem is to decide on what medium the script is being written on. If your culture is still in the Stone Age or Bronze Age, perhaps the majority of their writing is done on stone with a hammer and chisel. In this case, the shapes will be square or angular like in ealy Roman. If they use paint on canvas, the lines will be long and flowing to favor the constant use of a brush, which is seen in Asiatic scripts. If they have pens, the script will become considerably cleaner with more intricate shapes, and will likely develop a cursive font for the sake of expediency.

Aside from all that though, I think it’s just a matter of trying on designs over and over until it looks right. I’ve redesigned several of the letters in Ro’tehk, especially Eelule, Jahv, Leek, Kahk, Pike, Tave, and Zihf. I’m still juggling some of those around as I write more in the script and find better ways to match them to the style I’ve chosen.

When it comes to the writing structure itself, there are tons of creative decisions to be made, and it all comes down to what it is your culture wants to express. Maybe English systems just aren’t sufficient for the method of communication your culture wants to support. For example, Ro’tehk has had me ditch the use of periods, commas, and ending sentences with markers like exclamation points and question marks. It’s also had me design a system for the language to be written in any direction, and my only reasoning for these changes is that it’s “what the Ro’tehk would do”.

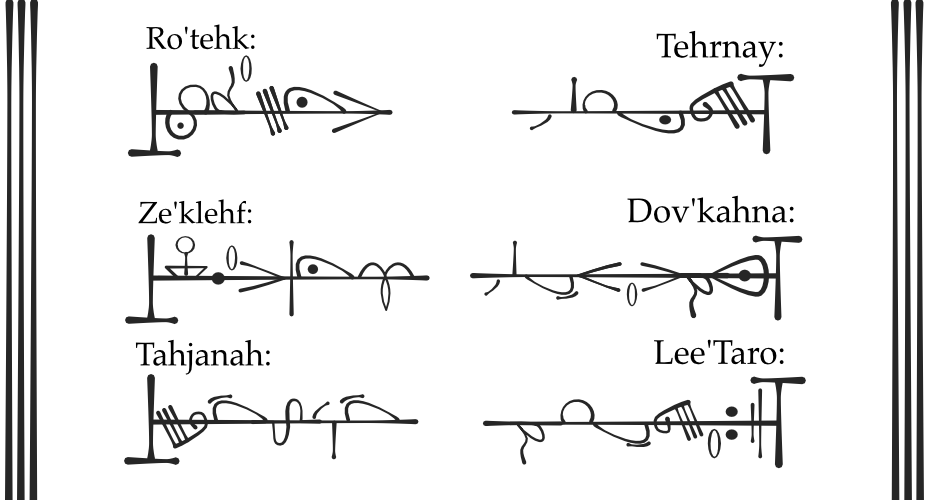

Ro’tehk uses a system of line roots to indicate which direction the script is oriented, which sentence is next in line, how each sentence is to be read, and where breaks in the sentence exist without the use of commas. They also use more markers. The three major punctuation markers we’re familiar with outside of periods and commas and such are the !, ?, and !?, but Ro’tehk has a larger pack of “mood modifiers” that I’m still tinkering with that add emotional intent to the sentence. These modifiers can be inserted in the middle of a sentence, or even in the middle of quoted dialog to emphasize the emotional context in small selections of text.

One of the biggest problems most of us are familiar with while texting and making social media posts is that much of the emotional subtext of speech is lost when reduced to writing, and that’s one thing that the Ro’tehk would try to get around. Again, this because they’re so detailed about the preservation of information and context. My design choices always come back around to what this culture deems important, which is why I made culture the first step in conlang development.

In your language, maybe the direction in which the script is written is how they signal certain emotions, or maybe it’s how they divide between inanimate and animated descriptions, or maybe they write in one direction when speaking of holy matters and another direction when speaking of everyday matters. The systems are there for you to do whatever you wish, and you can invent as many crazy rules and traditions as you want to fit the culture that your language belongs to.

The biggest reason Ro’tehk is designed to be written in any orientation is because of this one picture I have in my head of Ro’tehk murals, where the lines of the painting are actually lines of script that wrap and weave to form the lines of the picture. This way, the language both illustrates the images and tells the story of the subjects in the painting at the same time as a form of high art. These “Written Murals” inspired most of the rules behind this writing system, so all you need is one picture of how your culture uses its language to create something unique. A language is a tool, and tools are designed to complete specifc tasks.

Step 4: Create A Vocabulary

This is where the tedium of language building comes in, and I’ve only begun to tackle this step with Ro’tehk. There are thousands of words we use all the time that are essential for basic communication and thousands more that give depth to what’s being said. On top of this, there are dozens of modifications that will need to be applied to these words depending on the grammar of your language. An obvious suggestion for this step would be to make sure the most frequently used words are as small as possible since languages tend to cut down on words that are used every day.

Roots make this process of developing larger words easier, and Ro’tehk heavily relies on a system of roots to build ideas from. Root words in this culture are based on core concepts, feelings, or senses – which of course are all colored by the lenses of this culture. Root words are intentionally very, very broad and very vague so that the same root can be used over and over again for increasingly specific definitions. These roots are also very short in most cases so combining them into bigger ideas doesn’t create a twenty-five-character long word.

Here are a few examples:

Da [deI] = Evil / Foreboding / Shadow / Malice

Keh [kε] = To Toil / To Strive / To Enforce / To Make Real

Vi [vaI] = Air / Invisible / All Encompassing / Above

These roots then combine into Dakeh, which is “Evil Work/Force”, then the “-n” modifier is added to create Dakehn, which translates to “Demon”, or literally “Evil Toiler”. The second evolution of this is then Vidahk, a species of dog-sized, flying amphibians that are well known for their fast, mischievous, and destructive habits. Vidahk literally translates to “Air Demon” or “Invisible Troublemaker”.

As with all rules in language, you can use or ditch as many as you’d like. Ro’tehk is a very easy language for me to build specifically because this culture is scientifically minded in this regard. They try to make all their words conform to the same rules as often as possible, which should also make the language easier for other people to learn. The principles are reduced at any opportunity, so words are pluralized the same way, given tenses the same way, and made more complex in the same ways.

Step 5: Test Your Conlang

The only way to know if your language works and sounds the way you’d like it to is to try writing and speaking in it. You will find errors this way that you otherwise would’ve missed, and some words may not sound like you thought they’d sound in a sentence when actually spoken out loud instead of recited in your head. Writing the words on paper will help to naturally adjust glyph shapes as you intuitively try to get down the words faster and faster, especially if your script is brush or pen based.

That’s all I have for this article, but I hope to put out another one soon detailing the systems behind Ro’tehk. If anyone reading this has a conlang of their own to share, I’d love to see it and chat about the ideas you’re putting behind it!

Happy Reading and Writing!

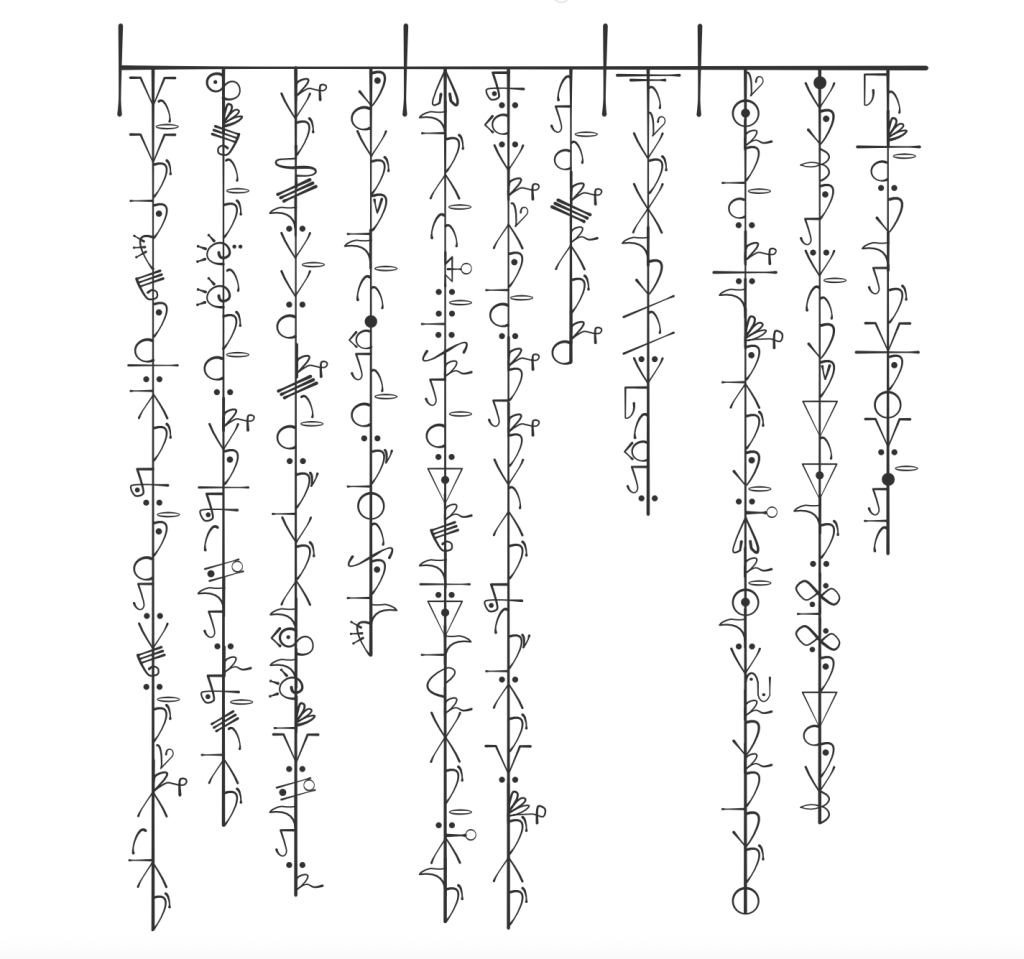

Ro’tehk, updated as of June 2022: