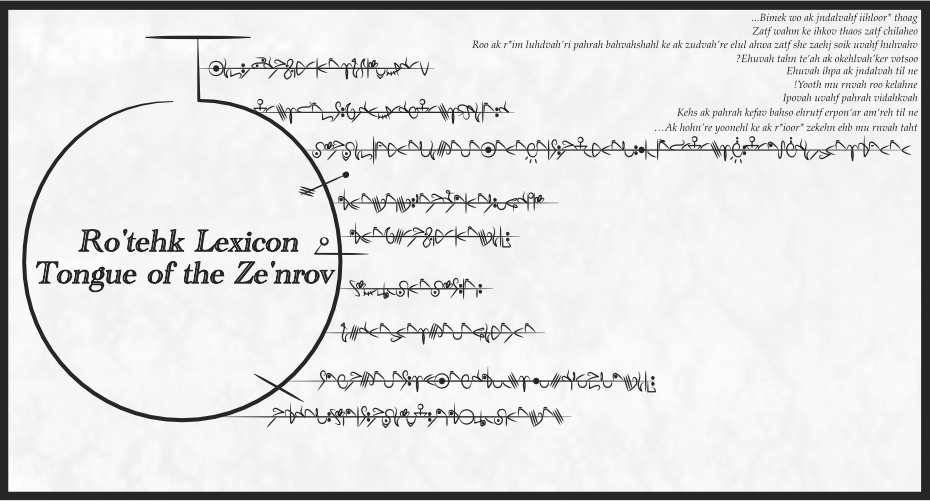

Zatf wahm ke ihkov thaos zatf chilaheo

Roo ak r*im luhdvah’ri pahrah bahvahshahl ke ak zudvah’re elul ahwa zatf she zaehj soik uvahf huhvahv

?Ehuvah tahn te’ah ak okehlvah’ker votsoo

Ehuvah ihpa ak jndalvah til ne

!Yooth mu rnvah roo kelahne

Ipovah uvahf pahrah vidahkvah

Kehs ak pahrah kefav bahso ehrutf erpon‘ar am‘reh til ne

…Ak hohn’re yoonehl ke ak r*ioor* zekehn ehb mu rnvah taht

…Touched by the Master’s golden venom

Her skin and eyes betray her allegiance

On the white wings of a great bahvahshahl and the men of the south at her back she will take your homes

?Will you stand along the roads in silence

Will you see the Masters return again

!Ride with us on Kelahne

Unleash your great vidahkvah

Use the great weapons against their servant in this dawn of their return

…The City of Glass and the Silver Angels will be with us all

I usually keep the details of my WIPs safe from big spoilers, but the Ro’tehk Lexicon is going to be the exception to that rule. I’ll be making the grammar, structure, some vocabulary, and the general development of this language open to the public through this blog post. If you have any comments or critiques, I’d love to hear them!

Version 2.3 – Updated July 14th, 2022

Current Lexicon Word Count: 335

Conlang Goals:

1. Ro’tehk is not intended to be an extremely difficult language to learn or decode. It has its differences from English, but I want it to remain familiar enough that it can still be approached. This language will play a fairly large role in the story it’s being written for, so I want any readers that may be interested in it to actually be able to understand it.

Besides, I already plan on building Vorisian after this, and that one will be a nightmare to read and speak for canonical reasons. No need to make two impossible languages, right?

2. I want this language to express the personality, history, and mindsets of its speakers. From the roots of their vocabulary to the written style of the script, it should be Ro’tehk through and through.

And that’s it. I want it to be tolerable to decipher, and true to the culture it’s built for.

Ro’tehk Phonemes:

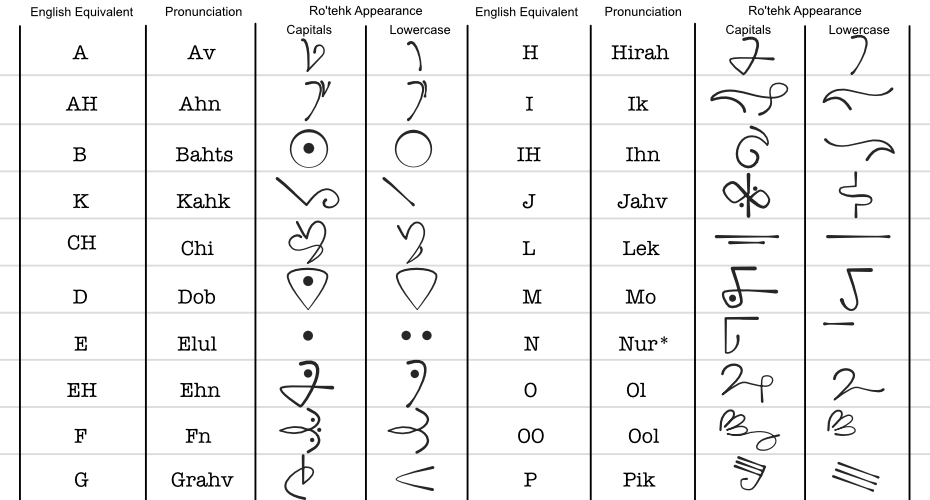

1. The Transcription Substitutes are what English letters and symbols are used when transcribing Ro’tehk text into English text. This is also called “Romanization”. This is most notable when vowels come into play. Any vowel standing without an “H” to its right is to be pronounced as the sharp version of that sound without exception.

2. The Glyph Names are the names of each Ro’tehk letter.

3. The Phonetic Pronunciations will be listed as defined by the International Phonetic Association.

| Transcription Substitute: | Glyph Name [pronounced]: | Phonetic Pronunciation: | Technical Classification: |

| A / a | Av [ave] | /eI/ | Dipthong |

| Ah / ah | Ahn [ahn] | /ɑ/ | Monothong |

| B / b | Bahts [bahts] | /b/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| K / k | Kahk [kahk] | /k/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| Ch / ch | Chi [chie] | /tʃ/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| D / d | Dob [dobe] | /d/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| E / e | Elul [ee-lool] | /i/ | Monothong |

| Eh / eh | Ehn [ehn] | /ɛ/ | Monothong |

| F / f | Fn [fn] | /f/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| G / g | Grahv [grahv] | /g/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| H / h | Hirah [hyrah] | /h/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| I / i | Ik [eye-k] | /aI/ | Dipthong |

| Ih / ih | Ihn [in] | /I/ | Monothong |

| J / j | Jahv [jahv] | /ʑ/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| L / l | Lek [leek] | /l/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| M / m | Mo [Moe] | /m/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| N / n | Nur* [nu-r*] | /n/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| O / o | Ol [ole] | /o̞/ | Monothong |

| Oo / oo | Ool [ool] | /u/ | Monothong |

| P / p | Pik [pike] | /p/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

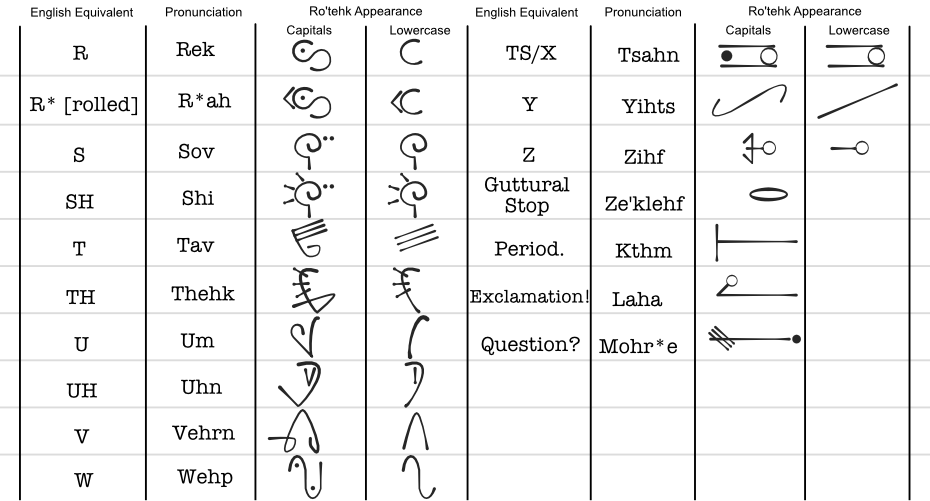

| R / r | Ret [reet] | /ɹ/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| R* / r* | R*ah [rolled ‘R’-ah] | /r/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| S / s | Sov [sove] | /s/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| Sh / sh | Shi [shy] | /ʒ/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| T / t | Tav [tave] | /t/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| Th / th | Thehk [thehk] | /θ/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| U / u | Um [oom] | /ʉ/ | Monothong |

| Uh / uh | Uhn [uhn] | /ə/ | Monothong |

| V / v | Vehrn [vehrn] | /v/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| W / w | Wehp [wehp] | /w/ | Co-Articulated Consonant |

| Ts / ts | Tsahn [tsahn OR xahn/ksahn] | /ts/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| Y / y | Yihts [yihts] | /j/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| Z / z | Zihf [zihf] | /z/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| ‘ | Ze’klehf [zee-klef] (Guttural Stop) | /ʔ/ | Pulmonic Consonant |

| … | Kthm [kthm] (“period”/neutral sentence mark) | ||

| ! | Laha [lah-hay] (exclamation/high energy mark) | ||

| ? | Mohr*e [moeh-r*-ee] (question mark) | ||

| -more coming soon- |

Ro’tehk Glyph Appearance

Spacing:

Spaces are added when transcribing, but there are none in the Ro’tehk script. Instead, capital letters separate words, which ends up looking like this: LookingLikeThis.

Spelling:

Spelling is cannonically regulated through the Archivists in joint with the Archeological Society in the Ro’tehk setting, and this means that all words sound exactly as they are spelled. Though plenty of slang exists outside of these spheres, all archived documents are corrected to meet this standard. Technically, the language being built here isn’t Ro’tehk, it’s Archival Ro’tehk, but maybe one day I’ll branch out into other dialects.

Ze’klehf Rules:

Rule 1.

When a ze’klehf appears before the first letter of a word, that letter is repeated twice. The word ‘Emnu is pronounced with two e’s, as in: E’emnu.

Rule 2.

Similarly, when a ze’klehf appears after the last letter of a word, that letter is repeated twice. The word Ka’ is pronounced with two a’s, as in: Ka’a.

Rule 3.

A line is added to the bottom of the ze’klehf if it is at the end of a word, and added to the top of the ze’klehf if it is at the beginning of a word. This way, the mark is not mistakenly associated with the next or previous word. If two words adjacent to each other happen to both end and then begin with a ze’klehf, only one mark is written and no lines are drawn on either side of the ze’klehf.

[Example pictures coming soon]

Rule 4.

All spoken ze’klehfs are written, but not all written ones are spoken. This is because ze’klehfs are used to adjoin words into larger concepts as well as mark guttural stops. The difference between these words often comes down to memorization, but when vowels are separated by a stop, it’s safe to assume that the stop is pronounced. Words like Pa’ah, Keh’e, and Ze’ene are all pronounced with guttural stops. However, the word M’tan does not use a verbal ze’klehf, and this is because the mark is being used to indicate the merger of the words Umook and Tan.

This is one area where common slang still exists even within Archival Ro’tehk, causing somewhat unnecessary memorization.

Line Roots & Writing Direction:

Line roots indicate the direction the text is being written in, which sentence is next in line, and act as anchors for new sentences to begin from. Mood modifiers and markers like question marks are also joined to the line root.

[Example pictures coming soon]

Commas:

There are no commas in Ro’tehk, or at least, there isn’t a glyph for it. This encourages Ro’tehk to have run-on sentences, using words like “with”, “and”, “for”, etc to continue to flow of thought. When there is a significant break in thought, the line is stopped and begins again from the line root.

[Example pictures coming soon]

Descriptive Order:

For reference, this is the English descriptive order:

Quantity or Number, Quality or Opinion, Size, Age, Shape, Color, Proper Adjective, Purpose or Qualifier, and then the Noun to which these descriptors are applied.

When put into a sentence, it forms:

Three beautiful giant old boxy green Spanish garden trees.

Now, that sentence is a little ridiculous since no one actually speaks utilizing every descriptor tag like that, but it’s the order all English speakers use without realizing that we’re using it. The Ro’tehk descriptive order is much different. It is based on the idea of stacking complexity and moving from objective measurements to subjective measurements:

Color, Quantity or Number, Size, Shape, Age, Noun, Proper Adjective, Purpose or Qualifier, Quality or Opinion.

This changes the sentence to read:

Green three giant boxy old trees Spanish garden beautiful.

Pluralization:

The majority of words are pluralized with “vah”, or in some cases, just “v”. Tehr becomes Tehrvah, and ‘Emnu becomes ‘Emnuv. In a minority of cases, “ahv” is also a pluralizer, such as Vin becoming Vinahv.

Possessive Modifier:

In English, we use (‘s) to mark possessive modifiers. The dog‘s chew toy, the boy‘s soccer ball, the sky‘s color. In Ro’tehk, the modifier (-f) is used. “The tree‘s branches” becomes Ak tehrf ehrkvah. “The woman‘s fruit” is Ak zajf ehmos.

Pronouns and Tenses:

There are two major types of pronouns: animate and inanimate.

Inanimate pronouns are extensions of the word Tsi, which is equivalent to the word “it”. It is used on inanimate objects, but is also used for wild animals, whereas domesticated animals or pets are granted animate pronouns.

Pluralizing this pronoun ignores the previous rule of pluralizing with “vah” or “v”, and instead becomes Tsime, which translates as “they” or “them”. To make this possessive, the word becomes Tsio for singular inanimate possessive (= to “its”), and Tsimeo for plural inanimate possessive (= to “their”).

Tsi = It

Ihtsi = It Is

Ehtsi = It Will

Etsi = It Was

Atsi = It Did

Tsio = Its

Ihtsio = Is Its

Ehtsio = Will Be Its

Etsio = Was Its

Atsio = Did Its

Tsime = They / Them

Ihtsime = They Are

Ehtsime = They Will

Etsime = They Were

Atsime = They Did

Tsimeo = Their

Ihtsimeo = Is Theirs

Ehtsimeo = Will Be Theirs

Etsimeo = Was Theirs

Atsimeo = Did Their

Some animate pronouns stem from the word Ze’ihn’ro, which is the equivalent to saying “homo sapien” in our own language. The slang for this is Ze’nro, which is like saying “human”. The “Ro’tehk” is the culture this language comes from, but the people speaking Ro’tehk are the Ze’nrov.

The letters “U” and “D” tend to be used for masculine pronouns and gendered words, and the letters “A” and “J” tend to be used for feminine pronouns and gendered words:

Zat = She / Her

Ihzah = She Is

Ehzah = She Will

Eza = She Was

Aza = She Did

Zaj = Woman

Zahj = Young Woman

Zahjehn = Girl

Zud = Man

Zuhd = Young Man

Zuhdahn = Boy

Zut = He / Him

Ihzuh = He Is

Ehzuh = He Will

Ezu = He Was

Azu = He Did

Similarly, tense and gender is also added to the word “I” to form:

Rn = I (gender neutral) (prnounced “urn”)

Rihj = I am (feminine)

Rehj = I will (feminine)

R*ej = I was (feminine)

R*aj = I did (feminine)

Rihd = I am (masculine)

Rehd = I will (masculine)

R*ed = I was (masculine)

R*ad = I did (masculine)

“Us / We” are similar:

Rnvah = Us / We

Rihv = We Are

Rehv = We Will

Rev = We Were

Rav = We Did

Pluralizing this once again breaks the “vah” and “v” rule from ealier. The root also changes from Ze’ihn’ro to Ehr.

Ehrum = They / Them (mostly male)

Ehram = They / Them (mostly female)

Ehrut = Their (mostly male)

Ehrat = Their (mostly female)

Ehrumih = They Are (mostly male)

Ehrumeh = They Will (mostly male)

Ehrume = They Were (mostly male)

Ehruma = They Did (mostly male)

Ehramih = They Are (mostly female)

Ehrameh = They Will (mostly female)

Ehrame = They Were (mostly female)

Ehrama = They Did (mostly female)

Ehrutih = Is Theirs (mostly male)

Ehruteh = Will Be Theirs (mostly male)

Ehrute = Was Thiers (mostly male)

Ehruta = Did Their (mostly male)

Ehratih = Is Theirs (mostly female)

Ehrateh = Will Be Theirs (mostly female)

Ehrate = Was Theirs (mostly female)

Ehrata = Did Their (mostly female)

“You”, singular, and “You”, plural, masculine and feminine:

Uv = You

Ihuv = You Are

Ehuv = You Will

Euv = You Were

Auv = You Did

Uvah = You All (feminine)

Ihvah = You All Are (feminine)

Ehvah = You All Will (feminine)

Eva = You All Were

Ava = You All Did

Uvuh = You All

Ihvuh = You All Are

Ehvuh = You All Will

Evu = You All Were

Avu = You All Did

Verb Tense:

In English, tense can often change the vowels in the word being modified. “Drink” becomes “Drank” to indicate past tense, but present tense usually just adds an (-ing) to the word, such as “Drinking”. However, words like “Squat” become “Squatted”, using the (-ed) modifier instead of changing “Squat” into something like “Squate”. Yet another example is “Fly” turning into “Flew”. Each word has its own rules for what indicates past, present, and future, which results in quite a bit of memorization.

In Archival Ro’tehk, the majority of words are given present tense with (-e) and past tense with (-ek). Uhni, Unie, and Uhniek, are respectively Sink, Sinking, and Sank. The same rule applies for Me’ehrm, Me’ehme, and Me’ehrmek, (Roll, Rolling, and Rolled); Diah, Diahe, and Diahek, (Rise, Rising, and Rose) and so on.

Sharp & Soft Vowels:

The Ro’tehk use only a handful of gendered words, but they have a secondary system that defines “future words” from “past words”. The Sharp Vowels, which define the past, include Av, Elul, Ik, Ol, and Um. Soft Vowels, which define the future, include Ahn, Ehn, Ihn, Ool, and Uhn.

Words that begin with a Sharp Vowel often describe things “of the past” or things that are “unchanging and continuous forces”. Words like Ka’, “Green”, Dakehn, “Demon”, and Opo, “Valley”, are prime examples of this mindset.

Conversely, words that begin with a Soft Vowel often describe things “of the now and future” or things that are “uncertain or incontinuous forces”. Words like Ahnkahve, “Snow”, Keh’e, “Fire”, and Kahnehth, “Lush”, are prime examples of Soft Vowel use.

Root Words:

Root words are the basis of the majority of Ro’tehk vocabulary. This is the current inventory of roots:

A’ah

Music / Rhythm / To Convey Emotional Clarity / Dance

Ah

Water / Cold / Darkness / Life

Av

Reflect / Copy / Mirror / Mock

Bohl

Smell / Fragrance / Stench / Breathe

Kan

Plants / Order / Cycle / Growth

Keh

To Work / To Strive / To Enforce / To Make Real

Keh’e

Fire / Light / Heat / To Wipe Clean

Chi

Bond / Trust / Friend / Rely

Da

Evil / Foreboding / Shadow / Malice

Dij

Through / Among / Amidst / Between

‘En

To Record / Save / Facts / Reality

Ehn

Creature / To Consume / To Remember / Fear

Ehr

Swarm / Many / Branches / Scattering

Fa

Pain / Anger / Blood / Fangs

Fil

Call / Beckon / Speak / Command

Gop

To Break / Tear / Rip / Gap

Huh

To Live / Nation / Family / Home

Huhda

Fog / Vapor / Smoke / Steam

Ihp

Sight / Imagination / Color / Eyes

Jyna

Origin / Root / Home / Loyalty

Len

Rough / Hard / Sharp / Aware

Looni

Shine / Sparkle / Glow / Shimmer

Luhk

To Fly / To Fall / Coast / To Ascend

Me’ehr

Circular / Roll / Spin / Loop

Nur*

Soft / Sleep / Safety / Nest

Ohm

Flat / Open / Wide / Expansive

Ov

Earth / Ground / Solid / Below

Oonah

Beauty / Wonder / Awe / Grand

Oovah

To Forget / Lost / Wander / Uncertain

Po

Control / Contain / Manage / Enslave

R*ish

Clean / Pure / Flawless / Smooth

Ser

Positive / Affirmative / “Is”

So

Harm / Wrong / Disrespect / Trespass

Tan

Tall / Slender / Pillar / Beam

Tho

Sickness / Poison / Curse / Death

Uh

Fall / Under / Slip / Accident

Vi

Air / Invisible / All Encompassing / Above

Vor

Negative / “Is Not”

Wak

Here / Location / Placed / Established

Wer*

Heavy / Load / Effort / To Drag

Tsoo

Sound / To Move / Listen / To Predict

Yehn

Small / Minuscule / Thin / Translucent

Yiht

Stay / Rest / Remain / Stillness

Yo

Fraction / Piece / Segment / Part

Za

Female / Feminine / Woman / Inner

Zah’i

Lightning / Speed / Leap / Strike

Ze

Good / Fortune / Joy / Peace

Ze’ihn

Time / Past / Future / Now

Zu

Male / Masculine / Man / Outer

2 Responses

🤯 Very cool! I’m impressed!!

Thank you!